The goal of the artificial pancreas developed by the Inreda Diabetic company in the Netherlands is to unburden people with diabetes. In the treatment of type 1 diabetes, it is crucial to avoid high and low blood glucose levels, keeping the levels ‘within range’. Out-of-range glucose can lead to acute and chronic complications. Currently, people with diabetes are preoccupied with keeping their glucose levels within range. The artificial pancreas assesses and regulates those levels automatically.

Robin Koops, Inreda Diabetic’s founder and owner, was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in 1995. Confronted with the daily discomfort of pricking, testing and injecting, and dissatisfied with the treatment he was receiving, he set out in search of a solution. The initial version consisted of two large machines. Later it became an apparatus the size of a shoulder bag, and it has meanwhile been shrunk to a small, portable device that the user can easily wear on the street.

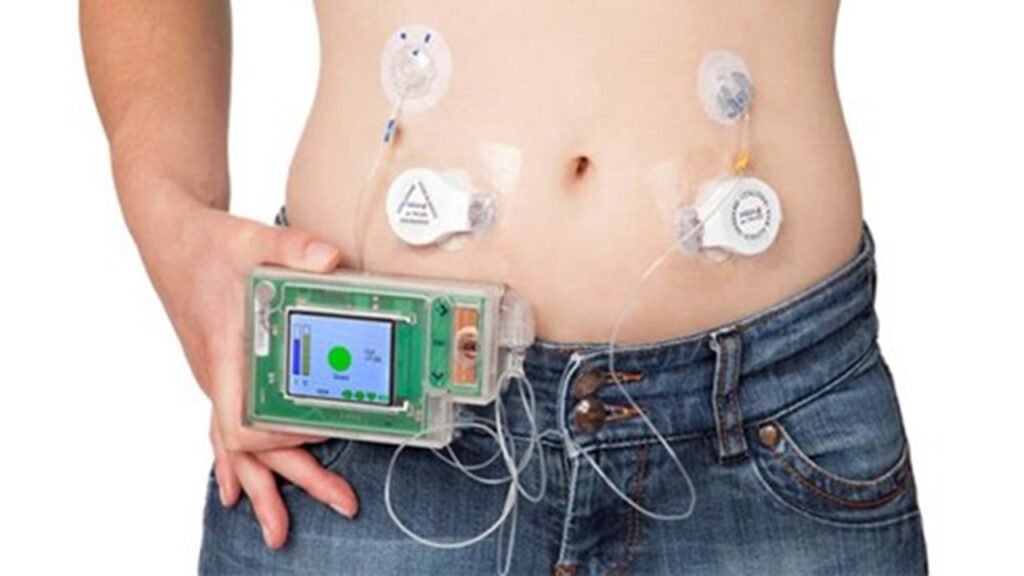

The artificial pancreas assesses the user’s blood glucose levels using two steadily functioning glucose sensors. Two tiny transmitters continuously transfer those readings to the artificial pancreas, which calculates the amount of insulin or glucagon that needs to be released, also taking current physical activity into account. Pumps are triggered, the correct doses of insulin and/or glucagon are released, the user’s glucose levels become adjusted, and a new assessment is made by the glucose sensors – this is known as a closed-loop insulin delivery system. Although Inreda is not the only company worldwide that is engaged in developing systems to simplify the lives of people with diabetes, it was the first European firm to develop a bihormonal system, which administers both insulin and glucagon, thereby correcting abnormal glucose levels both high and low. Moreover, the device employs a self-learning algorithm to adapt itself precisely to the person wearing it.

The medical world reacted cautiously at first, but persistence pays off. In the past 15 years, various prototypes have been rigorously tested and refined, in close collaboration with facilities including an Almelo hospital, the Rijnstate Hospital in Arnhem and the Amsterdam University Medical Centre (UMC). The flexibility of start-up enterprise and the receipt of various grants afforded room for manoeuvre. Research results are promising and trial users are upbeat. “Some participants reported that they briefly forgot they had diabetes.” The final clinical trial is underway, and the company expects to receive the European CE certification marking in mid-2019. It is meanwhile working hard to develop a smaller, lighter-weight model of the artificial pancreas to increase comfort and portability.

The company does not yet plan to enter the market on a large scale after obtaining CE certification. More research is planned, including necessary follow-up research on the use of glucagon and collaboration with the pharmaceutical industry to develop a stable variant of glucagon that users do not have to replace daily. Alternative possibilities for patient reimbursement are also being explored that would make the product accessible for all who need it.

Inreda recognises the huge step that users who opt for the device must take when they convert from diabetes self-management to fully automated treatment. A two-day training and coaching programme is provided, which familiarises users with the ‘ins and outs’ of the artificial pancreas. In addition to technical aspects, it focuses on topics such as psychological issues and the need for healthy lifestyles.

An artificial pancreas is expected to prevent or alleviate some of the acute and long-term complications of diabetes. The device therefore has the potential to substantially reduce the health care costs that are currently linked to diabetes.