There are now over 325,000 health apps for pretty much any aspect of care, health and prevention. That number includes great apps that unfortunately have not yet made it to mainstream healthcare as well as apps that utterly fail to deliver on their promise and may even be harmful. App stores barely assess the apps before putting them online. So how to separate the wheat from the chaff? It is difficult to answer that question without a standard and an efficient process for assessing health apps. Because of COVID-19 and the growing use and potential of health apps, it has become more relevant than ever to distinguish those ‘great apps’.

Ambiguity on the quality of health apps

The app landscape currently features health apps that constitute medical aids and apps that do not. An app developer determines the intended use of an application and is responsible for assessing whether or not that intended use is covered by the definition of a medical aid. Medical aids are subject to distinct legislation. In Europe, the Medical Device Regulation (MDR) replaced the Medical Device Directive on 26 May 2021. The MDR distinguishes between class I, IIa, IIb and III. Class I bears the lowest health risk, class III the highest. A developer of a class I health app can indicate that the app complies with the MDR by adding a CE label. Class IIa and up are subject to assessment by a recognised body to determine whether the app meets legislation and is allowed to be marketed with a CE label. The RIVM (Dutch CDC) performed an investigation into health apps in 2018[1]. A random sample revealed that 21% of the apps were medical aids. More than half of medical aid apps did not have a CE label. And several apps did have a CE label even though they did not constitute medical aids. Most apps do not qualify as a medical aid and are therefore not legally assessed.

Ambiguity on the quality of an app is being created in other ways as well. App stores may deny store access to certain apps. This is what happened to COVID apps to combat misinformation. However, they did not deny access based on the apps themselves, but rather based on the developer. If the developer was a university or government, the app was granted access. But if it involved a start-up or scale-up, access was denied[2]. In addition, developers have a lot of freedom when it comes to the app description and may opt for an academic tone to stimulate its use. But that does not equate to proof that the app delivers on its promise[3]. In short, it remains extremely difficult for consumers and healthcare professionals to gain a proper understanding of the quality of an app.

A standard for health and well-being apps

In an attempt to separate the wheat from the chaff, various organisations, or ‘app checkers’, developed methods both nationally and internationally in order to assess the quality and reliability of health apps. Results are often listed in an (in-house) app library: a website that displays the apps and their assessment results. Each app library has its own, often not very transparent, validation process and usually lists no more than several dozens of apps, sometimes a couple of hundred and in rare cases several thousand. Some validation processes do not involve the developer, others do.

Until recently, an international standard with widely adopted principles that health apps need to adhere to, able to contribute to a healthier supply of health apps and faster adoption of these apps, was lacking. This prompted the European Committee to assign the European Committee for Standardisation (CEN) to formulate a standard for the quality and reliability of health apps. A collaboration with ISO turned this into a global initiative that led to the formulation of CEN-ISO 82304-2[4]. In addition to existing standards for health software, development of the standard explicitly incorporated knowledge derived from the current practice of app checkers. The standard now allows for the quality and reliability of an app to be measured via a practical questionnaire to be completed by the developer. Furthermore, a certification procedure is being developed at the time of writing. It will stipulate who is authorised to assess the questionnaire and submitted argumentation, what the assessment will entail, when the argumentation is considered satisfactory and when an app – which is subject to constant change contrary to a pill – needs to be reassessed. The certification procedure will ensure that the assessment is uniform and sufficiently robust for wide recognition across borders.

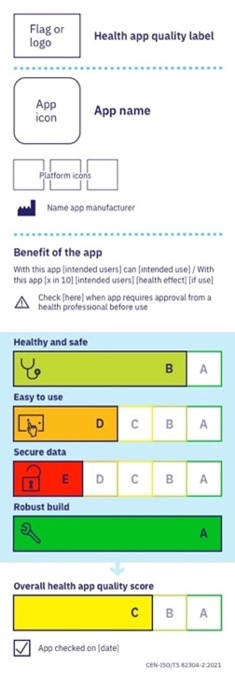

The developed method should make it easier to compare apps and make a selection. A label inspired by the EU Energy label, the Nutri-Score and the OTC drug label by the American FDA provides a summary of the report with an overall score. The standardised label for health apps offers a user insight into the quality of the application with much better substantiation than the present star ratings in app stores. Users make their own choice based on what they feel is appropriate for their specific situation. Comparable to the difference in quality requirements for a face mask used in public transportation versus the ICU.

Vocabulary to ease the adoption of digital healthcare

The standard supports health app developers in addition to helping patients, consumers and healthcare professionals in their selection. These developers are currently lacking a beaten path to stick to. And it often remains unclear what they need to do in order to get recommended by healthcare professionals or covered by health insurers. As it stands today, the latter remains reserved for a select few[5]. It can be quite staggering how much (unnecessary and expensive) research needs to be conducted before digital applications can be implemented. The healthcare industry lacks a standard measuring stick and suffers from ‘pilotitis’.

The standard offers a vocabulary to formulate minimum criteria for different types of apps. Because becoming part of mainstream healthcare remains difficult even for apps with sufficient scientific substantiation. Widespread use of health apps could lead to annual savings on European healthcare expenditures of €99 billion. And if widespread adoption turns out to improve our lifestyle and reduce absenteeism, the Gross National Product of the EU could improve by as much as €93 billion on top of that[6]. Plus, a standard ensures transparency for the end user. It removes existing barriers and stimulates the adoption and scaling up of proven apps at the international level as well as nationally. International recognition of the standard then accelerates the scaling up of an app across the borders of its home country.

More use of great apps

In the short term, we will be working on the certification procedure and the first implementations of the standard. The European Committee stimulates promotion and adoption of the standard and its label with the Horizon Europe subsidy[7]. Because in the end, it is not about the standard itself but rather what it can help us achieve: To make great apps an inherent part of mainstream healthcare. And to allow consumers to choose a great app for supporting their health based on sound information. A mutual standard can contribute to more transparency, increased (justified) confidence in apps and a beaten path for the adoption and scaling up of safe and effective eHealth applications in mainstream healthcare. With that, it stimulates a better offering of apps in all European languages and for all kinds of health-related situations that may face us at some point in our individual lives.

References

- Van Drongelen et al. Apps under the medical device legislation. RIVM. 2018

- Apple, Google, Amazon block nonofficial coronavirus apps from app stores. Cnet. March 15 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.cnet.com/tech/mobile/apple-google-amazon-block-nonofficial-coronavirus-apps-from-app-stores/

- Larsen et al. Using science to sell apps: Evaluation of mental health app store quality claims. NPJ digital medicine. 2019:2;18

- mHealth Hub European. Health apps repositories in Europe. August 2021. Retrieved from: https://mhealth-hub.org/health-apps-repositories-in-europe

- European Commission. Digital Health and Care: Transformation of health and care in the digital single market. Track 3: Digital tools and data for citizen empowerment and person-centred healthcare

- McKinsey & Company. The European path to reimbursement for digital health solutions. September 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/pharmaceuticals-and-medical-products/our-insights/the-european-path-to-reimbursement-for-digital-health-solutions#0

- European Commission. Socio-economic impact of mHealth – An assessment report for the European Union. PWC. 2013